Warning: This exhibit features content related to death, disease, and violence, including involving children and enslaved persons. Minors and individuals sensitive to these topics should proceed with discretion.

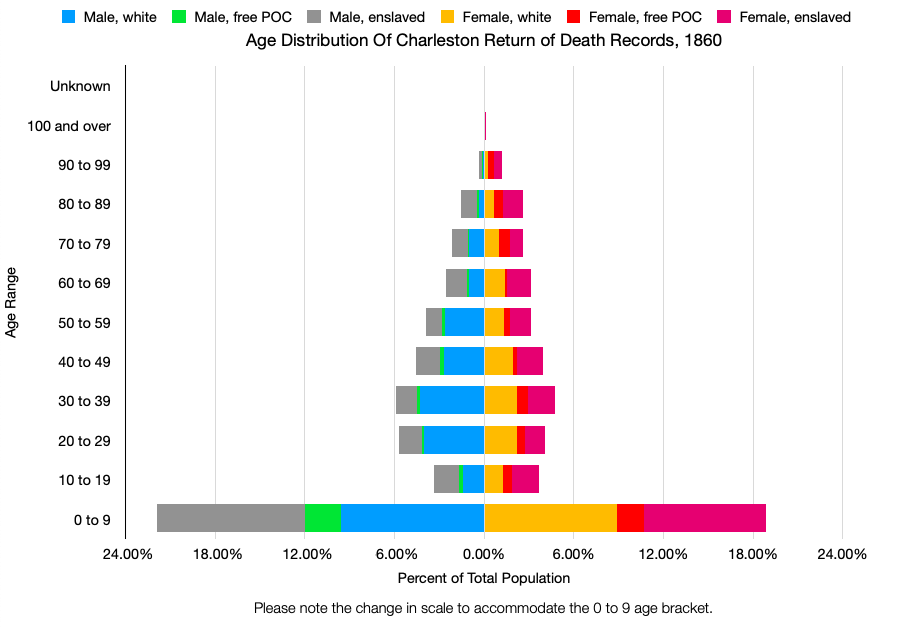

The map to the right features information about over 1,400 individuals who passed away in the City of Charleston in the year 1860. We'd like you, their modern-day neighbors, to meet them.

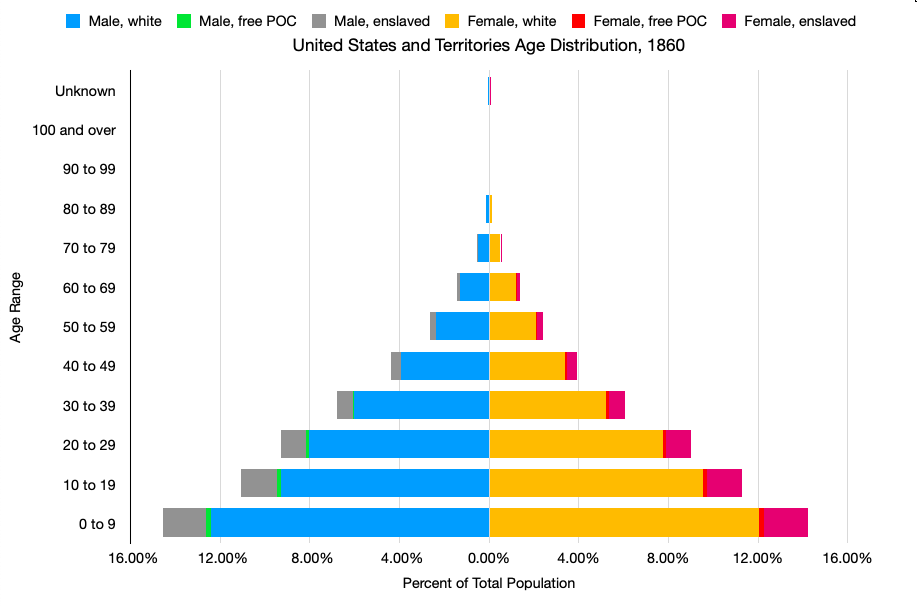

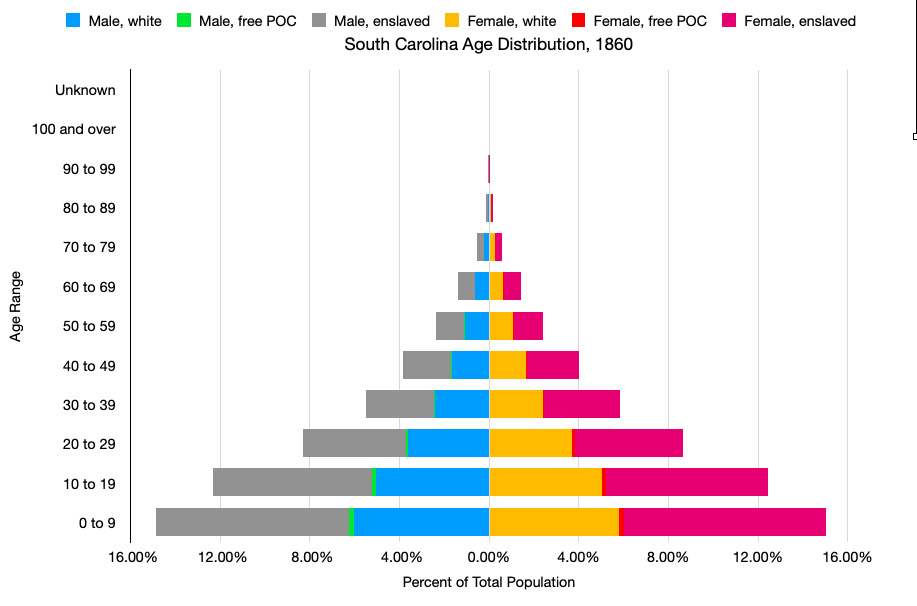

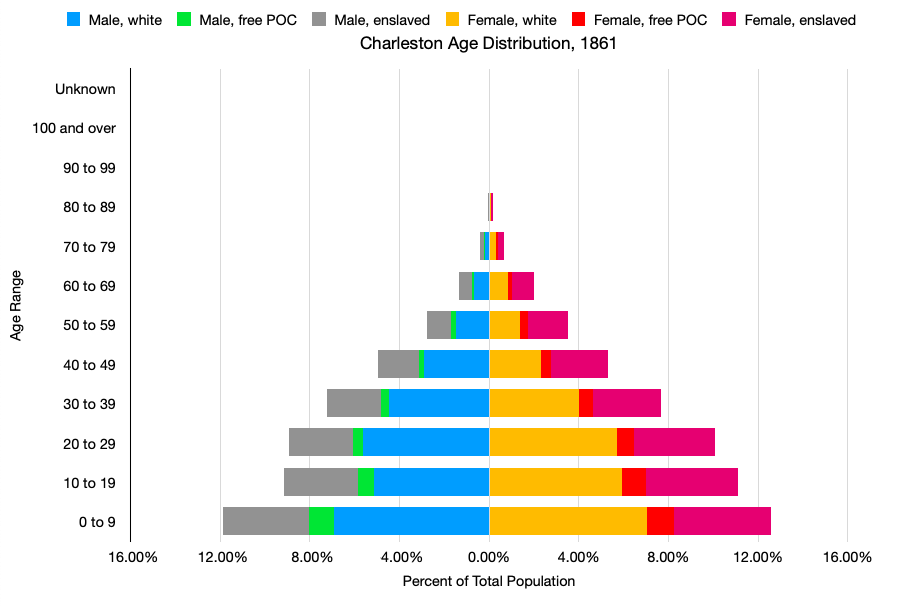

The year 1860 is featured because it a precipice for the history of the country and of Charleston. Two years earlier a yellow fever epidemic swept through the city, which physicians and other citizens were still grappling with along with the other diseases and perils constant to 19th-century life. By the end of the year South Carolina would no longer consider itself a part of the United States, and as the first state to secede and the future site of the first battle of the Civil War, Charlestonians were as keenly aware as anyone of the ramifications of national politics. And yet still the constants of everyday life carried on, including the "great equalizer" of death.

Besides the basic data of name, date, and cause of death, city health officials recorded what they considered to be the most important information about each person, including burial place, gender, race, enslavement status and name of enslaver, age, occupation, birthplace, street where they lived, and the name of their physician. We've included all the data given and presented it in a way that allows you to see trends and correlations and ask new questions about life in Charleston during this time.

Perhaps more than any time since 1860, right now we know what it's like to see Charleston in the midst of disease and unrest. And like our counterparts of 160 years ago, we continue to love and grieve and carry on. Maybe on the street where you grew up or around the corner from your favorite restaurant, people just like you lived and died and were a part of the ongoing story of the city. We hope you'll be able to see something of yourself in them, and see yourself as a part of that story too.

Click on each point to see information on the individual it represents. For larger points representing multiple people, click "Browse Features" and then use the left and right arrows at the top of the popup to scroll through each person. Please note that terms used correspond to information given in the records and some, like "mulatto," may not be appropriate for modern use.

The map that overlays the peninsula is from 1855, please see "Sources" for more information.

The green shapes are burial places listed in the records. Click on them for more information and to scroll through individuals interred there.

Filter: You can filter points on the map based on categories of your choosing, or use one of the preset options. Filters that you set are compoundable, so for example you can show just women, just white people, or just white women. For most categories you can also select more than one attribute, for example only showing people buried at Magnolia Cemetery or the Public Cemetery. Preset filters correspond to information given in the tabs below. The filter is defaulted to off, so be sure to toggle it on after choosing your criteria to see the results.

Time Slider: This shows a progressive time lapse of deaths throughout the year. This can be used in conjunction with filters, for example with a specific disease to show its spread across the city over time.

Legend: The colors of the data points represent the race of the person in the record, while the size of the point reflects the number of records for that location. As the records only record the street on which the person lived, not the exact house number, individuals living on the same street overlap and require a visual representation to show more than one person. This means that the exact location where each person lived will be more accurate on shorter streets like Henrietta Street, and less so on longer ones like King Street. Only a handful of records correspond to a precise location, like Roper Hospital or the Alms House. Grey indicates a group of people on the same street with no race in the majority. If you zoom in or out, the size of the clusters and the number of points clustered together will adjust.

Layers: Select this to toggle different layers on and off. For example, to see burial places without the data points, uncheck "Deaths 1860."

Swipe: Select this to easily compare modern locations with historic ones. Move the line across the screen and the 1855 map's visibility will change.

Share your thoughts on twitter or facebook using the links above and by using the hashtag #IIIExhibit. Also be sure to complete our visitor satisfaction survey.

To help spark conversation and give you food for thought, we've put together a few questions to consider while you explore this exhibit.

- What filter category seems most interesting to you? Burial place? Race? Occupation?

- Do any of these individuals seem like they could be related to each other? What story does that suggest to us?

- Who lived on streets where you live, work, or have visited?

- Do you notice any trends over time or space? By demographic?

- Are Black people more than, less than, or equally affected by illness as white people according to this data? Are children or adults?

- Did your family live in Charleston during this time? Could any of them be included in these records?

- Is there any information missing from these records? Anything that we can read "in between the lines?"

- If you were living in Charleston in 1860, where would you have lived and what would your life have been like? Do you recognize aspects of yourself in any of the individuals in this data?

- Are any strong or unexpected feelings brought up by any of this information? Do you need to step away for a moment?

- What were your preconceptions before exploring this information, and after?

- Does anything remind you of your community today, your neighbors or the social/political situation you live in?

- Are there any aspects of this information you'd like to learn more about?